What is Applied Sociology?

A brief introduction on applied sociology

By Dr Zuleyka Zevallos, 23 May 2009.1

The aim of this article is to broadly sketch what it means to be working as an applied sociologist. I begin with a general introduction into the discipline of sociology, before providing a definition of its applied branch. I then provide a concise background history of the different practices that might be considered under the rubric of ‘applied sociology’. Lastly, I present an outline of the professional skills that a degree in sociology can offer its graduates.

My discussion on applied sociology refers to those professionals who use the principles of sociology outside a university setting in order to provide their clients with an in-depth understanding of some specific facet of society that requires information gathering and analysis.

Applied sociologists work in various industries, including private business, government agencies and not-for-profit organisations. The work of applied sociologists is especially concerned with changing the current state of social life for the better. This can include anything from increasing the health and wellbeing of a disadvantaged community group; working with law enforcement organisations to implement a rehabilitation program for criminal offenders; assisting in planning for natural disasters; and enhancing existing government programs and policies.

I will show that a degree in sociology has several career benefits, but I specifically focus on the strong communication, research and interpersonal skills that prove advantageous to sociology graduates looking for work. I argue that applied sociology can help to improve any professional sector that might benefit from a critical evaluation of how a particular social issue, group or organisation works.

What is Sociology?

In a very general sense, sociology can be defined as the study of ‘the bases of social membership’ (Abercrombie, Hill and Turner 2000: 333). That is, sociology is the study of what it means to be a member of a particular society, and it involves the critical analysis of the different types of social connections and social structures that constitute a society. This includes questions about how and why different groups are formed and the various meanings attached to different modes of social interaction, such as between individuals or social networks; face to face versus online communications; local and global discourses, and so on.

Sociology also encompasses the study of the social institutions that shape social action. A social institution is a complex, but distinctive, sub-system of society that regulates human conduct (Berger 1963: 87). For example, the media acts as a social institution that can influence the way in which ‘facts’ are represented and interpreted; the law and politics impact on the ways in which different cultural groups define what is deemed ‘right’ and ‘moral’; the institutions of economy and education affect social status (that is, wealth and inequality among individuals); and the institution of family shapes our ideas about partnership, work, gender, sex, childrearing, and our bodies, as well as various other aspects of our lives.

Sociology can therefore be used to study all the social experiences that human beings are capable of imagining – from practices of childbirth, to the use technologies, to our attitudes and rituals regarding death – and everything else in between. People usually understand their problems in reference to their own personal life story and they are not always aware of the complex links between their own lives and the rest of the world’s history (Mills 1959: 5). The ‘sociological imagination’ helps us to make sense of the connections between history, biography and place (Mills 1959: 6).

Sociology allows us to study individual behaviour in a broader context, to take into consideration how societal forces might impact upon individuals, as well as the ways in which individuals construct the world around them, and how they manage to resist existing power relationships in order to achieve social change. In this light, sociology represents ‘a transformation of consciousness’ (Berger 1963: 21).

Sociology questions taken-for-granted assumptions about the world we live in (what we see as ‘familiar’ and ‘normal’ within the context of our everyday lives), and it provides a new and more critical perspective of the world, through the use of scientific theories, concepts and empirical evidence.

Sociology is often perceived as an academic profession, but there are many places outside of universities where sociology can be used to enhance personal and professional development.

A definition of applied sociology

Applied sociology is a term that describes practitioners who use sociological theories and methods outside of academic settings with the aim to ‘produce positive social change through active intervention’ (Bruhn 1999: 1). More specifically, applied sociology might be seen as the translation of sociological theory into practice for specific clients. That is, this term describes the use of sociological knowledge in answering research questions or problems as defined by specific interest groups, rather than the researcher (Steele and Price 2007: 4).

Applied research is sometimes conducted within a multidisciplinary environment and in collaboration with different organisations, including community services, activist groups and sometimes in partnership with universities. Some applied sociologists may not explicitly use sociological theories or methods in their work, but they may use their sociological training more broadly to inform their work and their thinking.

I will now go on to provide a broad overview of the history of applied sociology, including some of the professional roles that sociologists have traditionally taken on, and the variations of sociological practices that exist today.

History and applications of sociological practice

Harry Perlstadt (2007) traces the history of applied sociology to 1850, and the work of Auguste Comte, one of sociology’s founding figures. Perlstadt writes that Comte divided the discipline of sociology in two parts: social statics, the study of social order, and social dynamics, the study of social progress and development (2004: 342-343). Perlstadt argues that Comte’s theory lends itself to two types of sociologies: ‘basic research’ and social interventionism.

Basic researchers educate and influence public debate, and social interventionists are political activists who are responsible for actively enforcing social change (2004: 343). According to Perlstadt, Comte saw applied researchers as occupying a ‘translational role’ in-between these two positions. Nevertheless, almost 160 years later, there remains a long-standing divide between the so-called ‘pure’ and ‘practical’ research traditions in sociology. While these differences may appear to be artificial, ambivalence persists between academic and applied sociologies, despite the fluidity and intersections between these practices (see Gouldner 1965; DeMartini 1982; Rossi 1980).

Roles for Practitioners

Hans Zetterberg (1964) argues that ‘practical’ sociological knowledge might be distinguished into five roles: decision-maker, educator, social critic, researcher for clients, and consultant. First, the sociologist as decision-maker is someone who uses social science in order to shape policy decisions (1964: 57-58).

The sociologist as an educator is a person who teaches sociology to students, typically in a university setting (1964: 28-60), although sociology is now increasingly taught in high schools and as part of specialist courses.

The sociologist as a commentator and social critic is someone who writes for a wider public through books and articles aimed at an educated public, with a view of influencing public opinion (1964: 61-62).

The sociologist as researcher for clients might be someone who works with public or private organisations, such as mental health groups, banks, or some other company that commissions research on very specific topics (1964: 61-62).

Finally, the sociologist who acts as a consultant works to answer a specific and practical problem as defined by a particular client, using their client’s language and by making specific reference to their client’s problem, rather than a broader social problem or grand social theory (1964: 62-63).

Zetterberg positions applied sociologists as fulfilling the latter two roles: client work and consultancy.

Variations of Applied Sociological Practices

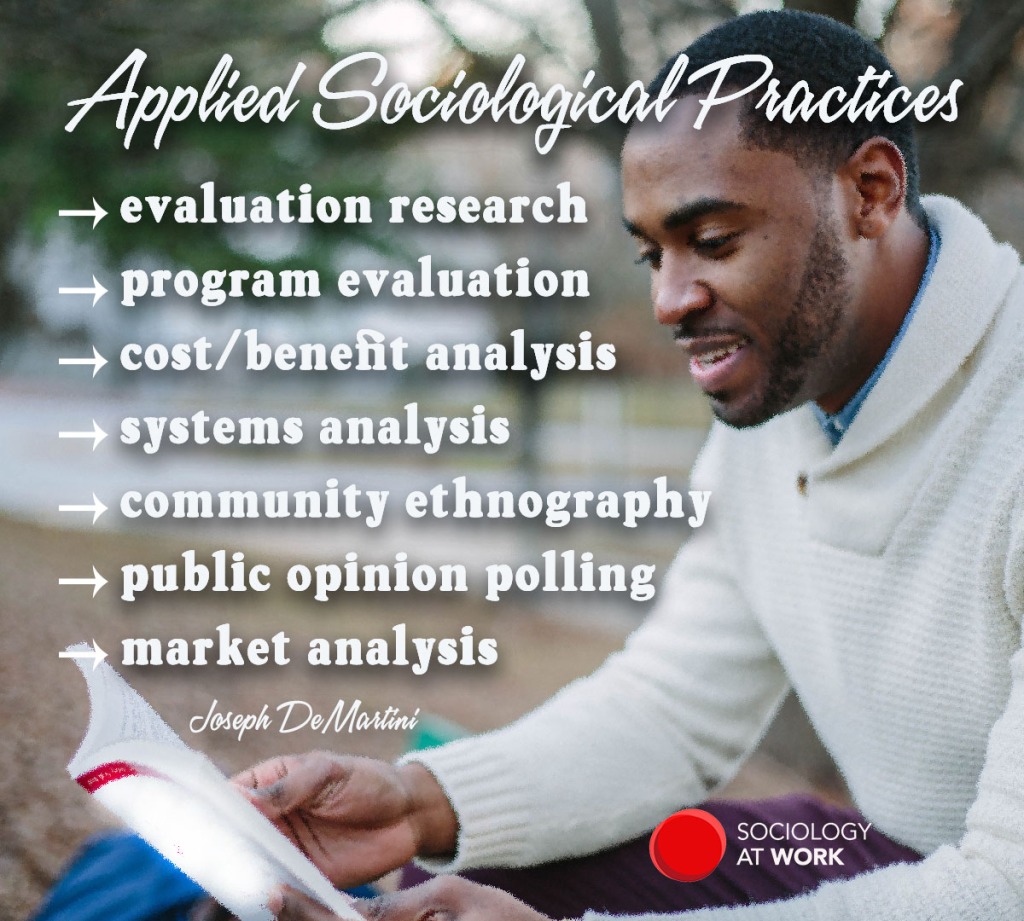

Joseph DeMartini (1979) identifies that applied sociology can take on two variations. First, applied researchers might use basic empirical methods in collecting information in order to help shape informed decisions, such as in the creation of social policy. In this meaning, sociologists might be directly working within government agencies, or they might work for private research organisations, or they might be contracted for one or the other. He lists the following activities as examples of this applied methodological approach:

‘evaluation research, program evaluation, cost/benefit analysis, systems analysis, community ethnography, public opinion polling, and market analysis’ (1979: 333).

While these sociologists might employ scientific theories and concepts, their specialisation is actually the application of sociological research techniques in order to gather specific information, rather than the application of sociological theories per se (1979: 334).

Second, applied researchers might be employed more specifically for their knowledge of sociological concepts and theories in order to help their clients better understand a narrowly defined issue. Activities might include assessing the determinants of observed phenomena, such as the causes of crime, explaining demographic changes, and evaluating the shifts in social movements.

Alternatively, applied sociologists might propose a course of action in order to achieve targeted change, such as by increasing the economic outcomes of a disadvantaged community, reforming illegal behaviours, or developing a framework in order to prepare a local community in the advent of a natural disaster (1979: 334).

To clarify the distinction between these two applied practices, DeMartini uses the example of social policy: in the first case, where methods take primacy, applied sociological research techniques are employed in order to create and inform new social policies; in the second instance, where theories and concepts have greater relevance to the clients, applied sociological knowledge is used to evaluate existing social policies.

DeMartini notes, however, that this differentiation is for illustration purposes, and that, in fact, applied practices run along a continuum in between these two practices (1979: 333). Methods and theories cannot be used in isolation, but some jobs might require more emphasis on one than the other.

Distinguishing Academic and Applied Sociology

Howard Freeman and Peter Rossi (1984) argue that the application of sociological knowledge is different for academic and applied sociologists. They see that some of the work that academics do might be considered to be ‘applied’, particularly as universities are seeking more external revenue, and so they encourage academics to carry out contract work. Nevertheless, by and large, Freeman and Rossi see that academic and applied sociologists are distinguished in six ways.

First, applied sociologists’ careers rely less on publishing in academic journals, and, instead, they focus more on the utility of their work to a specialised (non-academic) audience. Since, they are hired by external stakeholders, their rewards are judged by their sponsors, on the basis of whether these clients see the work as being useful to them (1984: 572). Academics rely more on peer-evaluations, and there is high prestige in publishing in academic journals.

Second, Freeman and Rossi argue that applied sociologists have narrow constraints on their time and the specificity of their work outputs, while academic sociologists are more free to choose their research topic (notwithstanding the politics of grant funding and the publishing potential of certain topics) (1984: 572-573).

Third, applied sociologists adhere to ‘absolute norms’ of rigorous scholarship ‘only to the extent necessary to achieve usable results‘ (1984: 573; my emphasis). There is sometimes a swift turnover expected of the work by applied researchers, while academics generally have a longer time-frame with which to develop their scholarship.

Fourth, applied sociologists are more concerned with ‘external validity’, that is, the extent to which their conclusions speak directly to their specific client’s topic area, rather than to some general social problem or broader group. Academics tend to focus more on ‘internal validity’ – to making a contribution to the academic literature, and the judgements of their peers (1984: 573).

Fifth, applied sociologists are driven by the ‘practical payoffs’ of their activities, such as their client’s judgement of the utility of this applied work to the client’s situation, while academics are required to defend the merits of their work in relation to their theoretical contribution.

In connection, the final difference between applied and academic sociologists is that the former judges the success of their work on their client’s adoption of their proposed solutions, and their ability to influence their stakeholders’ decision-making, while the conclusions proposed by academics do not always lend themselves to specific actions (1984: 573).

Freeman and Rossi’s distinctions between the work of academic and applied sociologists are, in reality, not so absolute, but these points do identify some of the broad facets of applied sociology.

In summary, applied sociologists work for specific stakeholders, their research topics and time is often constrained by their sponsors’ needs and wishes, their work is less concerned with making a contribution to academic scholarship, and they are more interested in practical payoffs that will have a direct influence on their clients.

Clinical Sociology

There are various other sociological practices that fall under the ‘applied’ rubric. For example, clinical sociology is a term that has been used since the 1930s to describe ‘sociologically based interventions’, usually in reference to sociological work done across the health sector, in social work, and even in forensic settings (Bruhn and Rebach 1996: 3). This work includes collaborating with medical practitioners, nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists and nutritionists, as well as advocacy and support in mental health programs, including through counselling, interpersonal therapy, intervention programs with youth, substance abuse services, and group grief counselling.

Social Engineering

The term social engineering describes the applied research activities that are used in social planning, and it is also used to critique the value judgements made about what constitutes ‘pure’ and ‘applied’ research (Gouldner 1965; Israel 1966). Jonathan Turner (1998) runs with the idea of ‘sociological engineering’ to describe the type of sociology ‘that tries to deal with the real world’ (1998: 246). He argues that applied sociological knowledge lends itself to a systems engineering approach. He sees that applied sociology should be used to break abstract theoretical principles into ‘rules of thumb’ about social structures, in order to identify how societies are built, how to evaluate the problems of a given social structure, and how to break down the structures that are not working well (1998: 248).

Whatever we choose to call it, applied sociologists’ use of methods and theories has one central goal: to change some specific facet of social life.

Public Sociology

One thing that practitioners seem to agree on is that their work needs to be carried out in a way that is both accessible to their clients and devoid of academic jargon. In this connection, applied sociology has some synergy with public sociology, the branch of sociology that aims to engage ‘lay’ audiences, including neighborhood groups and grassroots organisations, with the aim of stimulating informed public dialogue (Burawoy 2004: 5-6).

Rita Simon (1987) argues that communication skills are quintessential in an applied context; sociologists who work in non-academic sectors should therefore be able to express themselves in plain language and not in ‘sociologese’ (using phrases that only people with a sociology degree might understand). She writes,

‘Basically, I think graduate students have to be taught that scientific writing is not a thing apart from ordinary prose; the aim is still to communicate efficiently, effectively, and if possible, aesthetically’ (1987: 34).

The next section takes up this issue of graduate careers in applied sociology.

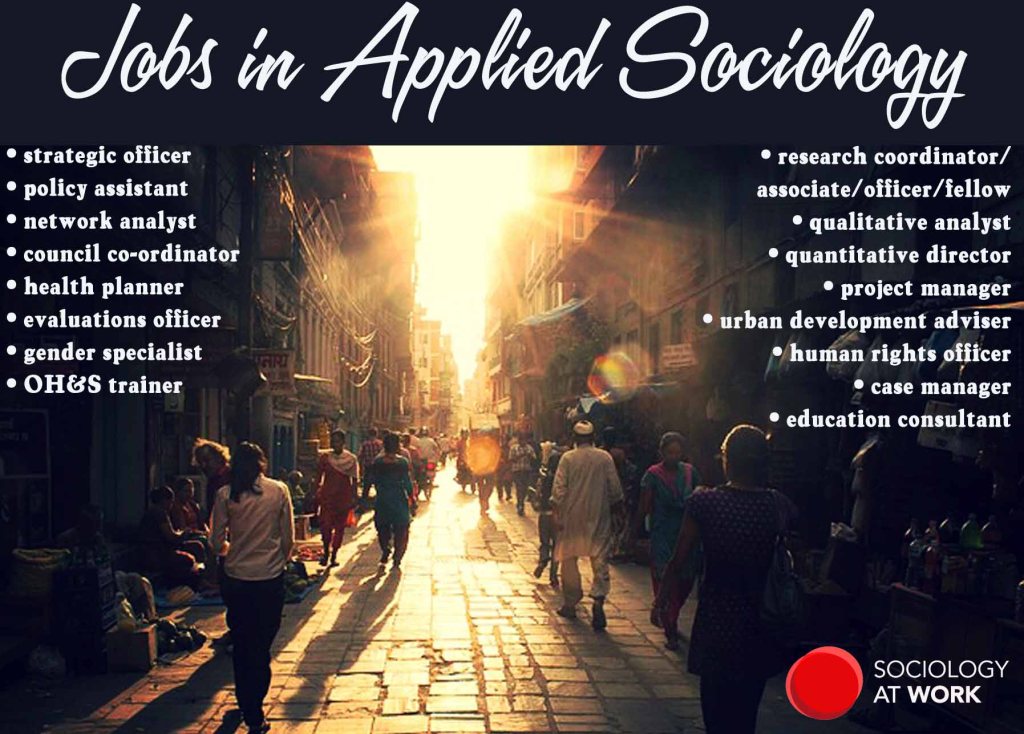

Jobs in applied sociology

Employers place a strong value in sociological training, including our methodological excellence in conducting research and analysis, our ability to evaluate a wide variety of resources, and our effective communication skills, both written and oral (Germov and Poole 2006: 12). Moreover, sociologists are trained to appreciate different world-views, and so our interpersonal skills also give us an advantage in the job marketplace (cf. Sabin 1987: 396).

Most job advertisements (at least in Australia) will indicate two requirements that are nowadays almost universal in professional sectors: reflexive social skills and the ability for workers to adhere to equity and diversity laws. Sociology graduates are well placed to get along with their co-workers, to respect diversity in the workplace, and to foster good client relationships with various different public groups due to our discipline’s comparative focus on other cultures, and our critical appreciation of social context (both in terms of history and place).

Despite their marketable qualities, sociology graduates do not always understand the types of career pathways available to them outside of academia. Few jobs that sociologists do are labelled under the category of ‘sociologist’. Nevertheless, the reality is that sociologists’ general skills are useful in a wide range of professional contexts.

For example, Edward Sabin (1987) writes that in Washington, USA, of the 1.6 million non-academic jobs that were listed in 1980, only 560 were identified as ‘sociologists’. The rest of the people in this sample were employed predominantly as professional and technical workers (113,640 people), systems analysts (19,850), and as writers and/or editors (8,690). A smaller proportion of workers were employed as public relations specialists (3,750), statisticians (2,870), statistical clerks (1,040), and urban and regional planners (760) (1987: 396). Sabin argues that the position of systems analyst holds great potential for applied sociologists, as it involves data processing, as well as an understanding of how organisations and businesses work. He writes,

‘Sociologists have a head start in understanding how people, procedures, and automated systems fit together, which is the focus of the systems analyst’ (1987: 397).

As far as the professional and technical workers category is concerned, Sabin sees that the general skills of a sociologist, rather than their specialist knowledge in one niche area (such as the topic of their thesis), is more likely to open up employment opportunities.

So, while employers may not advertise for ‘sociologists’, they might instead ask for the various roles identified above, as well as some of the positions listed below (although this is by no means an exhaustive list):

• research coordinator,

• research associate/officer/fellow,

• qualitative analyst,

• project manager,

• strategic analyst,

• public policy assistant,

• policy analyst,

• urban development adviser,

• human rights officer,

• case manager,

• impact planning or evaluations officer,

• education consultant,

• gender specialist.

Sociology graduates therefore need to have a broader understanding of the different types of career paths that are out there waiting for them, and they need to better recognise that sociologists can be employed in the most (seemingly) unlikely places. For further discussion of applied sociology in the Australian context, and some examples of these practitioners’ work, see our online journal, Working Notes.

Conclusion

Applied sociological work can fit in well within any professional context; wherever people work, sociologists can help them grow by better understanding their business, their workers, their work practices, or whatever issues are of interest to their organisation. Rather than having a narrow focus on the types of companies and groups that might hire sociologists, sociology students and the wider public need to better recognise that sociologists are employed across a multitude of business, government and private industries. The quality of their work is exemplary, and, moreover, it can make a substantial contribution to the way the world works.

Further Resources

Visit our Working Notes section to read articles about applied sociology written by applied sociologists, or watch our videos with applied researchers and activists. See our other resources.

Notes

1. At the time of writing, Zuleyka was employed as a Social Scientist in the Australian public service, and she was an Adjunct Research Fellow with the Swinburne Institute of Social Research, Australia. She remains in her Adjunct position but now works as an applied sociologist elsewhere. This article was last updated 5th June 2014: added sub-headings and images. Paragraphs broken up into smaller chunks. Added Further Resources section. No text in the body of the article has been otherwise altered.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Lucy Nelms for commenting on an earlier draft of this article.

References

Abercrombie, N., S. Hill and B. S. Turner (2000) The Penguin Dictionary Of Sociology, 4th ed. London: Penguin Books.

Berger, P. (1963) Invitation To Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective. New York: Anchor Books.

Bruhn, J. G. (1999) ‘Introductory Statement: Philosophy and Future Direction’, Sociological Practice 1(1): 1-2.

Bruhn, J. G. and H. M. Rebach (1996) Clinical Sociology: An Agenda For Action. New York: Plenum Press.

Burawoy, M. (2004) ‘Public Sociologies: Contradictions, Dilemmas, And Possibilities’, Social Forces 82(4): 1-16.

DeMartini, J. R. (1979) ‘Applied Sociology: An Attempt At Clarification And Assessment’, Teaching Sociology 6(4): 331-354.

DeMartini, J. R. (1982) ‘Basic And Applied Sociological Work: Divergence, Convergence, Or Peaceful Co-existence?’, The Journal Of Applied Behavioural Science 18(2): 203-215.

Freeman, H. E. and P. H. Rossi (1984) ‘Furthering The Applied Side Of Sociology’, American Sociological Review 49(4): 571-580.

Germov, J. and M. Poole (2006) ‘The Sociological Gaze: Linking Private Lives To Public Issues’ pp. 3-20 in J. Germov and M. Poole (Eds) Public Sociology: An Introduction To Australian Society. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Gouldner, A. W. (1965) ‘Explorations In Applied Social Science’, pp. 5-22 in A. W. Gouldner (Ed) Applied Sociology: Opportunities And Problems. New York: Free Press.

Israel, J. (1966) ‘Remarks On The Sociology Of Social Scientists’, Acta Sociologica 9(3-4): 193-200.

Mills, C. W. (1959) The Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press.

Perlstadt, H. (2007) ‘Applied Sociology’, pp. 342-352 in C. D. Bryant and D. L. Peck (Eds) 21st Century Sociology: A Reference Handbook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Rossi, P. H. (1980) ‘Presidential Address: The Challenge And Opportunities Of Applied Social Research’, American Sociological Review 45(6): 889-904.

Sabin, E. (1987) ‘Hidden Jobs: Good News For Sociologists’, The American Sociologist 18(4): 394-399.

Simon, R. J. (1987) ‘Graduate Education In Sociology: What Do We Need To Do Differently?’, The American Sociologist 18(1): 32-36.

Steele, S. F. and J. Price (2007) Applied Sociology: Terms, Topics, Tools And Tasks, 2nd ed. Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth Publishing.

Turner, J. H. (1998) ‘Must Sociological Theory And Sociological Practice Be So Far Apart?: A Polemical Answer’, Sociological Perspectives 41(2): 243-258.

Zetterberg, H. L. (1964) ‘The Practical Use Of Sociological Knoweldge’, Acta Sociologica 7(2): 57-72.

Image Credits

1) Banksy.

3) Jusben Morgue File.

4) Banksy.

5) Mu-Am-Spring2008 (2008) Faces of Athens- Sociology Project. Flickr.

6) Michele0188 (2011) Hopeful the Egyptian Government will listen. Flickr.

7) Antsnax (2009) SCARE TSBVI Volunteers. Flickr.

8) Banksy.

Pingback: Sociology for Clients | Sociology at Work

Pingback: Applied Sociology Roles, Skills and Methods – New S@W Series | Sociology at Work

Pingback: Erotic Capital & Beauty: How Sociology Can Help Explain Desire & Sex Appeal | The Other Sociologist - Analysis of Difference... By Dr Zuleyka Zevallos

Pingback: A Note on Academic (Ir)relevance | Political Violence @ a Glance

Pingback: Sociology for What, Who, Where and How? Situating Applied Sociology in Action | The Other Sociologist - Analysis of Difference... By Dr Zuleyka Zevallos

Pingback: Where to Look For Contract Research Work | Sociology at Work

Pingback: Career Planning in the Research Sector – The Other Sociologist