Writing for Bloomberg View, American Professor of Finance, Noah Smith, reviews a sociology discussion paper exploring the social networks and earnings of economists. The original paper, by sociology Professor Marion Fourcade and colleagues Etienne Ollion, and Yann Algan, finds that economists are better positioned materially to both benefit from, and influence, economic policy because they work in business schools as well as in lucrative consulting firms.

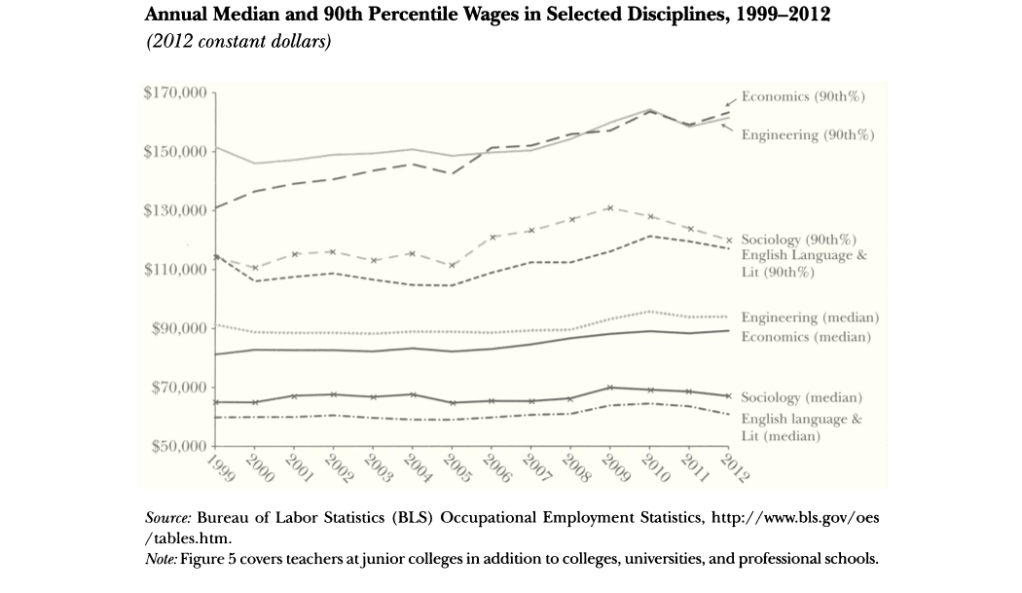

Smith argues that sociologists are out of touch with market demands (such as producing statistics), and we earn less as a result.

Applied sociologists earn less because we mostly work in low-paying – though no less important – fields, such as social welfare and health policy.

Applied Sociological Work in Economy

Notwithstanding the fact that sociologists also work with statistics, this does not make our non-statistical research any less relevant. We work within health and community sectors, providing much needed data and advice on how to improve social services. We work for not for profit agencies, shaping education policy, addressing unemployment and economic outcomes, and improving programs for disadvantaged groups. We work in government departments focusing on consumer rights, helping local councils to improve the business sector, and we also work alongside economists adding social insights that are very much in demand.

Applied sociologists work on a plethora of social welfare policy issues. We may not be paid as much for our economic policy work and consulting, but this doesn’t mean our work does not have value. Applied sociologists go into under-funded areas that sustain economic and social productivity, looking after public health and society’s most vulnerable. All of this is vital economic work.

Economists may have better social capital by virtue of who they work with and where they work. Social capital is a measure of how symbolic resources, such as social ties (networks or who we know), have a significant impact on maintaining or increasing material capital (wealth and other assets). In turn, this leads to increased income, power and influence.

Economists have links to high-paying clients and influential businesses. Their social networks pay off: they make more money, even if their research areas overlap with applied sociology.

Social Capital and Inequality Within Economics

So how do economists achieve this social capital? The study by Fourcade and colleagues shows that studies by economists are insular:

“The field is filled with anxious introspection, prompted by economists’ feeling that they are powerful but unloved, and by robust empirical evidence that they are different.”

Moreover, while 73% of sociologists agree with the statement, “In general, interdisciplinary knowledge is better than knowledge obtained by a single discipline,” only 42% of economists agree. Conversely, 57% of economists strongly disagree with this statement, while only 25% of sociologists disagree. This shows that sociologists are more open to interdisciplinary collaboration while economists are much less so. Why might this be?

Fourcade and colleagues’ analysis shows that this insularity helps to maintain power and influence. Less interdisciplinary collaboration keeps their social capital in high demand within high-paying circles.

Fourcade and colleagues also find that economic journals have an inbuilt “home bias” in that their high impact journals are based in elite, well-funded universities, where economists cite one another. Sociologists do not show this specific bias; applied sociologists in particular are likely to publish in non-sociology journals and for policy and public audiences that are no measured by academia. As such our influence may go unnoticed by the academy, but it doesn’t mean it’s not important.

Fourcade and colleagues also show that economics has a tighter career guidance structure for students. As a result, sociology graduates go into a plethora of applied fields, while economics majors are funnelled into a narrower career path, which favours economic rationalism. Fourcade and colleagues write:

For example, two-thirds of sociologists say that corporations make too much profit, but only one-third of economists and virtually no finance professors think so. The overwhelming majority of sociologists (90 percent) endorse the proposition that “the government should do more to help needy Americans, even if it means going deeper into debt,” but barely half of the economists and a third of the finance scholars agree with that proposition.

Smith fails to recognise that women are significantly disadvantaged in the discipline of economics. The field is dominated by older, white male professors.

Not all economists are happy with the status quo. They want to challenge the representation of economic knowledge and they tackle social issues like gender inequality. Fourcade and colleagues’ research presents an opportunity to rethink gaps within the social structure of economics as a field of study, by encouraging reflection on inequalities and demonstrating room for interdisciplinary collaboration.

Smith has not engaged with the social issues presented in Fourcade’s paper. Instead, he dismisses sociology because we make less money and in his eyes, because we can’t make the same impact on the economy. He writes:

If politicians want to know how to reduce cancer rates, they should go to a biologist. If they want to know how to shoot missiles at Vladimir Putin, they should go to a physicist. If they want to know how to boost productivity at U.S. companies, or increase employment, or auction off broadcast spectrum rights, whom should they ask for advice? A sociologist?

The economy is more than making money. It is about building social infrastructure and looking after the future wellbeing for all. Writing in 2013 in response to austerity budget discussions in Australia, Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz argues:

…National debt is only one side of a country’s balance sheet. We have to look at assets – investments – as well as liabilities. Cutting back on high-return investments just to reduce the deficit is misguided. If we are concerned with long-run prosperity, then focusing on debt alone is particularly foolish because the higher growth resulting from these public investments will generate more tax revenue and help to improve the long-term fiscal position… Instead of focusing mindlessly on cuts, Australia should instead seize the opportunity afforded by low global interest rates to make prudent public investments in education, infrastructure and technology that will deliver a high rate of return, stimulate private investment and allow businesses to flourish.

Applied sociologists address the economy beyond material capital, even if we’re not paid as much to do it.

Learn More

Some theory about how economic sociology shapes the new political landscape: Professor Michael Gilding, The new economic sociology and its relevance to Australia.

Discover more from Sociology at Work

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.