Happy new year, colleagues! This post highlights the broad-ranging impact of sociology beyond university settings. We look back at some examples of public sociology from the past year, and news of sociologists forging social change around the world. We showcase sociologists working in politics, economics, migration, the community sector, media, and beyond.

These stories were featured on our social media throughout 2025. If you’d like to get regular news on the impact sociologists make in the world, join us on BlueSky, @SociologyAtWork.bsky.social, or our community on LinkedIn.

TW: Child abuse.

Sociologists in the news

British sociologist Michael Burawoy was killed in a hit-and-run on 3 February 2025. In his final interview, he says public sociology remains relevant on key global issues, such as the Israeli genocide in Palestine. He says:

“I’ve been particularly in awe of Sociologists for Palestine, most of whom are assistant or associate professors, who have come together to work out how to defend the Palestinian struggle as members of the US academic community. They have been very successful, efficiently organised. They achieved what has never happened: an ASA Resolution for Justice in Palestine. Those doing this know that it may lead to sanctions. But if we recognise that public sociology is a form of education, speaking out beyond the university also performs an educative function.”

American sociologist, Associate Professor Zachary Levenson, reflects on Michael Burawoy’s public sociology:

“Public sociology was an orientation to the world. It wasn’t about dropping scientific findings and just leaving them there, hoping that research alone could change the world. No, for Michael, research was certainly part of the approach, but it was equally about all of things I have described in this essay. It was about sharpening our collective thinking and understanding the power of working in the institutions in which we’re situated, but always going beyond them.”

In March, Israel’s Education Minister did not allow the Israel Prize to be awarded to Moroccan French sociologist, Professor Eva Illouz, because she signed a 2021 petition urging the International Criminal Court not to trust Israel to investigate its own war crimes.

In July, for the centennial celebration of Orlando Fals Borda – the father of Colombian sociology – Borda is remembered as a “community-oriented, and critical actor.” He co-developed the methodology of Participatory Action Research, alongside his wife, María Cristina Salazar.

“Today, his legacy extends beyond grand academic halls. His principal enduring lessons are: a Sociology of Commitment, in the sense of understanding that science is not neutral, and the researcher can—and must—ally with the populations they document without losing rigor.”

In August, another centennial celebration, this time for Frantz Fanon. Tunisian sociologist, Frej Stambouli’s recollection of his experience being Fanon’s student has been republished:

“In particular, he [Fanon] made you realise the ferocity of the colonial system and the necessity to fight against barbarity, violence, and injustice. As first-year students of sociology, it was for us an unsurpassable introduction to our future specialisation.”

At the end of September, Turkish sociologist, Dr. İsmail Beşikci, who spent 19 years in Turkish prisons for his analysis of the colonisation of Kurdish people, was hospitalised after suffering a cerebral haemorrhage. (No further update as of 3 January 2026).

On 1 October, German sociologist, Steffen Mau, was appointed Director to the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity in Göttingen – Institute. His strategic focus will be issues of social inequality, conflicts, and the transformation of democracy.

On 3 November, two sociologists were arrested in Iran without reason or charges: “Mahsa Asadollahnejad, a sociologist and researcher, and Shirin Karimi, a sociologist and translator, were arrested by security forces and taken to an undisclosed location.” Less than a week earlier, on 27 October, Asadollahnejad gave an interview on a report criticising how the Iranian legal system handles rape victim cases. She said that the “humiliation [of rape] is ‘the deepest wound’ and that indifference allows it to spread.” For further context on this arrest, see the Letter to Iranian authorities regarding arrests and harassment of independent scholars, and for other writers and scholars in detention, see the Centre for Human Rights in Iran. Scholars at Risk reports that Asadollahnejad was released on bail on 12 November, after serving ten days in detention.

On 22 December, Polish sociologist, Marcin Zarzecki, was appointed to Poland’s Monetary Policy Council, which sets the central bank’s interest-rate.

Social change

On 30 January, during a keynote to the International Economic Forum of Latin America and the Caribbean, American sociologist, Jeremy Rifkin, proposed the term “Aqua Planet.” This phrase reflects the climate crisis and water shortage we face globally: “We are facing an extinction event, the likes of which has not been seen in 360 million years. 50% of species could disappear during the lifetime of today’s children.”

In March, Australian sociologist, Dr Stephen de Weger’s, research estimates up to 50% of Catholic priests may be engaged in sexual misconduct with adults. Priests who abuse children are four times more likely to be “sexually involved” with women and twice more likely to be “sexually involved” with men. Dr de Weger says: “We cannot effectively respond to this issue unless there are clear guidelines as to what we are dealing with here.”

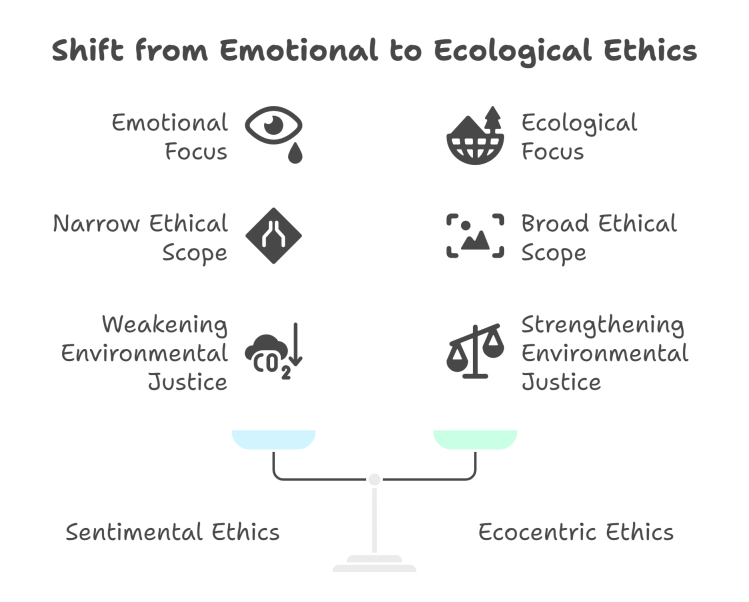

In mid-September, Iranian sociologist, Associate Professor Mahdi Kolahi, wrote about how sociology can help environmental activism shift from emotional logic to ecological ethics: “We must undertake a rethinking of values within environmental movements.”

At the start of October, American sociologist, Dr Andreas Reckwitz, wrote on loss, in the New York Times:

“The ideal of modern society is freedom from loss. This denial is Western modernity’s foundational lie… As the experience of loss contradicts the modern promise of never-ending progress, a general sense of grievance prevails.”

In early October, American sociologist, Jennifer Gunsaullus, finds that millennials and Gen Z are embracing “lavender marriages.” This arrangement, where queer people partner with heterosexual friends, is a response to financial burden, but also provides the benefit of platonic companionship. She argues this can “erase the very real and often painful reasons these marriages existed.”

In October, Argentinian sociologist, Professor Claudia Bacci, discusses Hannah Arendt’s impact on Latin America political movements:

“I think that the power of this idea today, encapsulated in Arendt’s idea of the ‘right to have rights,’ exceeds the specific significance that she had attributed to it in her work The Origins of Totalitarianism… The refugee and immigration crises, the persecution of advocates for Indigenous lands and of activists against extractivism that have been sweeping Latin America have been going on for decades. So, the demand for the ‘right to have rights’ persists today.”

American sociologist, Professor Stephen Whitehead says that, contrary to current conventional wisdom, masculinity is not in crisis. Instead, sociology shows that some men struggle due to their rigid gender ideals. “Male fundamentalism is an unapologetic, explicitly anti-female, misogynistic position adopted by men.”

In early November, American sociologist and Hamilton actress, Ashley LaLonde, discusses why Gen Z women are disengaging from Christianity. “Younger women were seeing some of the harmful impacts and legacy of hyper legalistic purity culture.”

In mid-November, First Nations sociologist from Australia, Gomeroi woman, Dr Sheelagh Daniels-Mayes, discusses her BlakAbility project. Using culturally safe yarning methods, Dr Daniels-Mayes documents the lived experiences of disabled Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in higher education.

“That’s what BlakAbility is trying to do, is to get this message out there that we are strong as Black people. We are strong as people with physical, sensory, psychological, neurodivergent, whatever differences. We’re a whole rainbow of difference, really.”

Politics

In mid-February, South African sociologist, Professor Nicky Falkof, analyses the U.S.A.’s Trump Administration policies granting refugee status to white Afrikaner South Africans, while withdrawing aid from South Africa:

“White victimhood refers to a powerful set of beliefs that treats white people as special and different, but also as uniquely at risk… The South African case is important because it plays a central role in global white supremacist claims. These mythologies claim that white South Africans, specifically Afrikaners, are the canary in the coalmine: that the alleged oppression they are facing is a blueprint for what will happen to all white people if they don’t ‘fight back.'”

At the end of March, Malaysian sociologist, Professor Ahmad Murad Merican, on the Israeli genocide of Palestinian people:

“Neutrality is not an option… The genocide in Gaza demands a critical reckoning of the role of sociology as a discipline and the broader purpose of academic institutions.”

At the end of March, American sociologist, Dr Brittany Friedman, discusses her book Carceral Apartheid: How Lies and White Supremacists Run Our Prisons: “Carceral institutions are the foundation and bedrock of any social system that is based on racial and ethnic division that uses violence to maintain it.”

In late April, American sociologist, Michel Anteby, on why the U.S.A. Trump administration’s plan to fire policy workers weakens democracy:

“If Weber’s insights and my observations are any guide, bureaucrats are also the safeguards that stand between the public and dilettantism, favouritism and selfishness.”

At the end of April, Togolese sociologist, Dr Koffi Améssou Adaba, discusses the Afrobarometer study, conducted in 39 African nations, which shows a decline in trust in public institutions across Africa over the past decade.

“Institutional trust is vital for political stability and effective governance, regardless of whether a regime is democratic or authoritarian. Even authoritarian governments seek some level of popular support to strengthen their power… The observed decline in trust could undermine the legitimacy of governments and might hinder development, particularly in developing countries.”

In mid-September, South African sociologist, Professor Ashwin Desai, reflects on the legacy of fellow sociologist, Fatima Meer. Meer interviewed over 1,000 women and 260 men on their experiences during apartheid. In a public address, Desai says: “But, for Meer, history was not a match of extractions and ideologies, but a human event of complicated and often tragic outcomes.”

At the end of October, Scottish sociologist, Professor Andrew Ross, supports the Peace and Democratic Society Process in Turkey: “The Turkish government cannot squander this historic opportunity to turn a peace agreement into a new and vibrant multiethnic order.”

In early November, American sociologist, Professor David Meyer, gave an interview on the “No Kings” protests in the USA: “There’s good reason for concern about backsliding, as the president has ignored Congress and lower court decisions.”

At the start of November, French sociologist, Professor Jean-François Bayart, discussed global youth protests: “Gen Z is not homogenous, nor necessarily ‘sympathetic.’ It can uphold values of justice and freedom, but also reactionary and violent ones… Gen Z should be analysed sociologically.”

Indonesian sociologist, Professor Ida Ruwaida Noor, says students are suffering trauma and are reluctant to return to school following SMAN 72 Jakarta attack on 7 November.

In mid-November, an article about Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni draws on the work of British sociologist, Sara Farris,’ work on “femonationalism,” arguing that Meloni, “employs feminist rhetoric and appeals to certain left-wing social causes to serve her broader far-right populist political agenda.”

In late November, Iranian sociologist, Dr Hamed Haji Heidari, discussed resistance movements: “The social capital of resistance has transcended national borders.”

In mid-December, Kenyan sociologist, Assistant Professor Siguru Wahutu, reflects on his research on media and genocide:

“As an African, I think there’s a moral imperative to remind people that Africans do tell stories and often tell amazing stories. But also, is it possible to tell contextually nuanced and relevant story about human suffering? What does that look like? And what are the politics of that? How do they think about their own role in archiving contemporaneous history and the process of witnessing these terrible events for people in their home audiences?”

Economics

In March, Canadian sociologists, Associate Professor Nathanael Lauster and colleagues, find young Canadians who live in cities with high rent costs (such as Toronto and Vancouver) are less likely to form their own households, in comparison with youth living in low rent cities (such as Quebec).

In late March, American sociologists, Assistant Professor Diana Sun and Professor Emeritus Michael L. Benson, find that white-collar offenders find it easier to secure employment and housing compared to non-white-collar counterparts. However, white-collar offenders had higher anxiety about social stigma, especially Black men.

At the end of March, American sociologist, Dr Neil Gross, discusses research showing that young Americans who voted for President Trump are relatively progressive on social issues, but are more motivated by economic concerns: “Long-term social change doesn’t automatically translate into electoral success.”

In April, Australian sociologist, Dr Dan Woodman, on intergenerational inequity: “…[T]oday’s young people could become the first Australian generation to suffer lower living standards on some key measures than their parents.”

In May, Japanese sociologist, Professor Atsushi Miura, argues that China will reach the fifth consumption era before Japan. The first consumption era was typified by urbanisation, the second by mass consumption, the third by individualism, and the fourth by minimalism: “The fifth consumption area (2021-2043) is characterised by solitude, sustainability, and new community, according to Miura.”

In August, American sociologist, Professor Daisy Verduzco Reyes, finds that, regardless of their income, Latin millennials in the U.S.A. are committed to caring for their parents, even if it limits their economic mobility.

“The one idea that none of the respondents questioned was the cultural imperative of the immigrant bargain, the idea of taking care of your parents. Some might expect this ‘burden’ to feed resentment, but none of my respondents expressed any such feelings.”

At the start of November, American sociologist, Professor David Harding, discussed jobseeker disclosure of past criminal history: “When the employer saw the ‘economic motivation’ narrative… they were more likely to want to choose the candidate with the [criminal] record.”

In early November, Ukraine sought to rebrand its money to move away from Soviet legacy. “A recent poll by the International Institute of Sociology in Kyiv showed that more than 90 percent of Ukrainians now view Russia negatively.”

The rest of these stories are from mid-November.

Bulgarian sociologist and President of the Gallup Institute (London), Kancho Stoychev, says Bulgaria will “drown in debt with the 2026 budget”: “Everyone knows that the debt crisis is ahead of us and with this budget we are taking a decisive step towards the abyss.”

American sociologist, Professor Francesco Duina has co-edited the book, The Social Acceptance of Inequality: On the Logics of a More Unequal World, which explores four ways in which different cultures come to accept inequality. The “logics of acceptance” are: market/economic, moral, group, and cultural. He says that in his “Economic Sociology” class, he asks:

“How many of you would want perfect equality? …Nobody raises their hand. They’ve never thought of that. So, where are you and why? Why do you accept some degree of inequality?”

Chinese sociologist, Xu Lingling’s, new book, The Time Inheritors, examines time use and its relation to class. Wealthy people reach educational and job milestones quickly and with relatively low stress, while poorer people have a “debt-paying mentality,” as they struggle to repay family sacrifices. “Substantial time wealth can cultivate a very secure relation with time — a sense of security, assuredness, and entitlement about the future.”

In mid-November, British sociologist, Dr Tom Roberts, was interviewed on the news about environmental waste dumped by organised crime gang in River Cherwell, England: “It is the most lucrative career move… the penalties if you get caught are much less severe, and you’re much less likely to be caught.”

American sociologist, Professor Allison Daminger, interviewed 170 women, who discuss the gendered cognitive load of family life. “Women endure higher anxiety and burnout, but what I didn’t expect to find was lower political participation related to the level of burden they are carrying at home.”

Migration

In early October, New Zealand sociologist, Professor Paul Spoonley says that the number of New Zealanders moving abroad is unprecedented. “Every year for the last 30 years, we’ve seen more New Zealand citizens leave New Zealand than arrive, but it’s really spiked in the last year… [to] over 70,000.”

At the start of November, Romanian sociologist, Associate Professor Marius Matichescu, finds Romanians, especially in Timis County, show high support for migrant workers:

“Romania is no longer just a transit country. It is no longer just a country where immigrants come and go, but a country where immigrants want to settle. They want to settle in Timisoara, because in Timisoara, respectively in Romania, life is better than in many other parts. And I am referring here to Western Europe.”

In early November, Icelandic sociologist, Professor Þóroddur Bjarnason, argues Keflavík International Airport has become a major bottleneck for travellers: “For people with higher education and good incomes, ease of access to an international airport can be a deciding factor in where they choose to live.”

In mid-November, Indonesian sociologist, Dr Andreas Budi Widyanta’s, research shows Indonesian migrant workers are vulnerable to online gambling and scams:

“The data we see is just the tip of the iceberg. Behind it are countless families losing their homes, land, and belongings to pay off debts caused by online gambling… Basic digital competency education should be a compulsory training requirement before they go abroad, and the government must oversee its implementation.”

At the end of November, Albanian sociologist, Gëzim Tushe, discusses ongoing issues with emigration: “Many people left Albania… in the hope that the magnet of the West… would create the possible conditions for more freedom, for more equality, for more prosperity.”

Community

If we didn’t know better, we might think that 2025 was the year of the third space, with no less than three media articles drawing on American sociologist, Ray Oldenburg’s, theory.

In October, a British article on corner cafes in London draws on Oldenburg’s work:

“The city’s most powerful innovation hubs are not tucked away in corporate towers or polished accelerator spaces; they thrive in its cafés, pubs, and co-working lounges. These places, often overlooked, function as what sociologist Ray Oldenburg called ‘third spaces’: informal, accessible environments where ideas flow freely and unexpected collaborations spark. They are the unsung engines of London’s creative and economic dynamism, quietly shaping the city’s future one conversation at a time.”

In November, another article on Oldenburg’s third spaces, this time on community group, the Highgate Society: “Think of the shortcuts people make across the grass: third places are the social equivalent, forming wherever people naturally want to meet.”

And again, in November, another third space shout out. Canadian sociologist, Tonya Davidson’s new book, Ottawology, draws on her introductory sociology courses and PhD research. She explores what makes the city of Ottawa unique, as well as exploring its third spaces, including diver bars, libraries, parks, and shopping centres:

“Urban sociologists ask questions like: How do cities offer opportunities for ecologically sustainable living? How do strangers interact when living so closely together? What makes cities more or less functional, and who are they made functional for?”

Media and popular culture

In May, British sociologist, Dr Alice Evans, features in a New York Times podcast, discussing global fertility declines and its connection to technology use.

“So if we look empirically at the data for a range of countries, we find that an increasing number of people are staying single. That is, they are neither married nor cohabiting… we’re all retreating into this digital solitude. I think that’s partly because technology makes it nicer and easier to stay at home — you can work from home — and some of these apps are so hyper-engaging that you get distracted by the constant stream of dopamine hits as each app, as each technology company competes against others to keep its users hooked. And effectively, the tech is outcompeting personal interactions. That’s my fear.”

In June, Chinese Australian sociologist, Pan Wang, explains the TikTok “Boy Sober” trend, where young heterosexual women are staying single by choice. “Women are rejecting marriage because of the unequal distribution of domestic work, male chauvinism, and intense social pressure.”

Also in June, Japanese-Polish sociologist, Yasuko Shibata, discusses the potential for classical music and Romanticism to shape social revolution. “The values of Polish Romanticism could encourage some Japanese people to boldly express their opinions and to protest against the powerful system, which often suppresses the lives of individuals.”

In October, for Halloween, Canadian sociologist, Alex Bierman, discusses the sociology of fear: “We feel we’re not in control of the circumstances, and scary movies, scary books, they give us a sense to feel the sense of powerlessness, while at the same time knowing that really, we aren’t powerless.”

In September, American sociologists, Associate Professor Shiri Noy, Dr Christopher P. Scheitle, and Dr Katie Corcoran, find Americans are increasingly drawn to astrology to make sense of their lives during times of uncertainty. One-quarter of Americans believe in astrology, and one-third of Americans have consulted horoscopes. The researchers drew on nationally representative surveys and interviews.

“From a sociological perspective, astrology is fascinating precisely because it straddles categories. Rather than a set of cosmic beliefs, many people treat astrology as a tool — part spirituality, part cultural practice, part entertainment and part language for understanding themselves and others.”

In November, American sociologist, Professor Susan Brown, speaks about her research on marriages that end after age 50:

“I was thrilled to be invited to share my research on grey divorce on a national stage with the iconic Oprah Winfrey leading the discussion.”

Again in November, American sociologist, Professor Mitchell Duneier, analyses the themes of the biopic, “Springsteen” on the New York Times: “What is obscured by the nostalgic narrative about a lost golden age of American manhood: Today’s crisis didn’t begin with the loss of manufacturing jobs, and simply bringing those jobs back won’t solve it.”

Discover more from Sociology at Work

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.