As we near the anniversary of his death, we look at the achievements of Norwegian sociologist, Professor Johan Galtung (24 October 1930 – 17 February 2024). He is known as the ‘father of peace studies.’ In 1987, he was awarded the Right Livelihood Award (also known as the Alternative Nobel Prize), ‘For his systematic and multidisciplinary study of the conditions which can lead to peace.’ Over 70 years, Galtung mediated more than 150 conflicts at the local, state, national, and international levels.

Brief timeline of achievements

Below is an abridged timeline of key events and accomplishments.

1940: Germany invades Norway. Galtung’s father, an ear-nose-throat surgeon, operates on soldiers, regardless of nationality. This leaves a ‘deep impression‘ on nine year-old Galtung to ‘save lives, anyone’s life, without distinction.’

1944: Galtung’s father is taken to a Nazi concentration camp in Norway. He is released on April 1945, further shaping Galtung’s commitment to anti-war work.

1954: Jailed in Norway as a Conscientious Objector to military service, after completing 12 months of civilian service. He was 24 years old. During his six-month imprisonment, he co-authored his first book with his mentor Arne Naess, Gandhi’s Political Ethics (1955).

1956: Completes PhD in mathematics from the University of Oslo.

1957: Completes PhD in sociology from the University of Oslo.

1958: Mediates his first conflict, over desegregation in the school system in the USA southern states. He was teaching mathematical sociology at Columbia University at the time.

1959: Establishes the Peace Research Institute Oslo.

1964: Co-founds the International Peace Research Association.

1967: Publishes Theory and Methods of Social Research.

1969: Launches the Journal of Peace Research at the University of Oslo.

1987: Receives the Right Livelihood Award.

1993: Founds TRANSCEND, a network for Peace and Development, which still operates today.

Theory

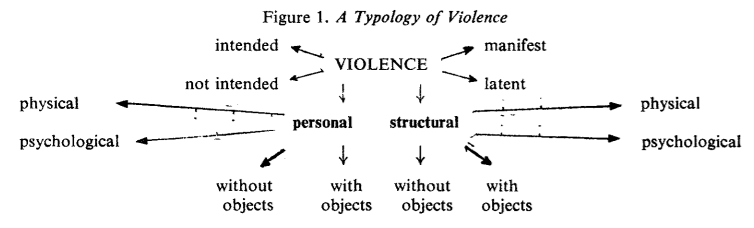

In his foundational work, published in 1969, Galtung focused on three principles underpinning his theory of peace:

– Johan Galtung (1969: 167)

- The term ’peace’ shall be used for social goals at least verbally agreed to by many, if not necessarily by most.

- These social goals may be complex and difficult, but not impossible, to attain.

- The statement peace is absence of violence shall be retained as valid.

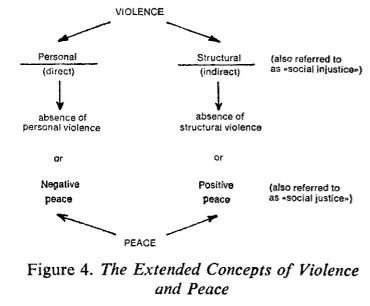

In the same publication, he additionally developed the concept of ‘structural violence,’ to capture non-direct acts of violence, such as starvation, disease, neglect, inequality, and the lack of freedom and democracy, all of which contribute to political instability.

Galtung establishes two forms of peace:

- Negative peace: the absence of personal violence

- Positive peace: the absence of structural violence

In 1990, Galtung introduced the concept of ‘cultural violence.’ This term describes the ideological justifications for violence through nationalism, racism, sexism, and other forms of structural discrimination embedded in social institutions.

Method

Galtung developed the TRANSCEND methodology, a three-step approach to peace negotiation:

- Confidence-building: Establish individual dialogue with all parties. Seek to understand goals, fears, and concerns. Build trust.

- Reciprocity-relations: Distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate goals. The former affirms human needs, such as self-determination. The latter violate human needs, such as domination.

- Identification of gap: Bridge the difference between contradictory goals, through mutually acceptable, sustainable solutions.

The TRANSCEND Manual is guided by a sociological approach (‘socio-cultural analysis’). Galtung writes:

‘To live in a peace structure it has to be relatively solid, “institutionalised” as sociologists would say, and the peace culture has to be “internalised,” accepted’

– Johan Galtung (2000: 6)

Other research

Galtung’s other theoretical and methodological contributions include:

- Conflict analysis and peace theory

- Comparative civilisation theory

- Development theory

- A new approach to economics addressing ecological balance

- Structural-cultural-behavioural theory of violence

- Peace-building methodology using diagnosis-prognosis-therapy

Peace-building as applied sociology

Galtung established peace studies as a transdisciplinary practice (going beyond existing scientific fields to create a new perspective or epistemology). Applied sociology is central to this, alongside economics, political science, and anthropology. In 2010, he writes:

‘Sociology, focusing on interaction and structure, is by definition more relational and hence structural and hence better suited for understanding how violent relations and structures produce more violent relations, and what a peace structure among persons and groups might look like.’

– Johan Galtung (1990: 22)

He then adds:

‘Sociology contributes the observation that interactional processes or relations can be beneficial or not, equitable or not, and that they can combine into structures in many ways, often with pyramids (hierarchical structures) and circles (cyclical processes) as building blocks.’

– Johan Galtung (1990: 24)

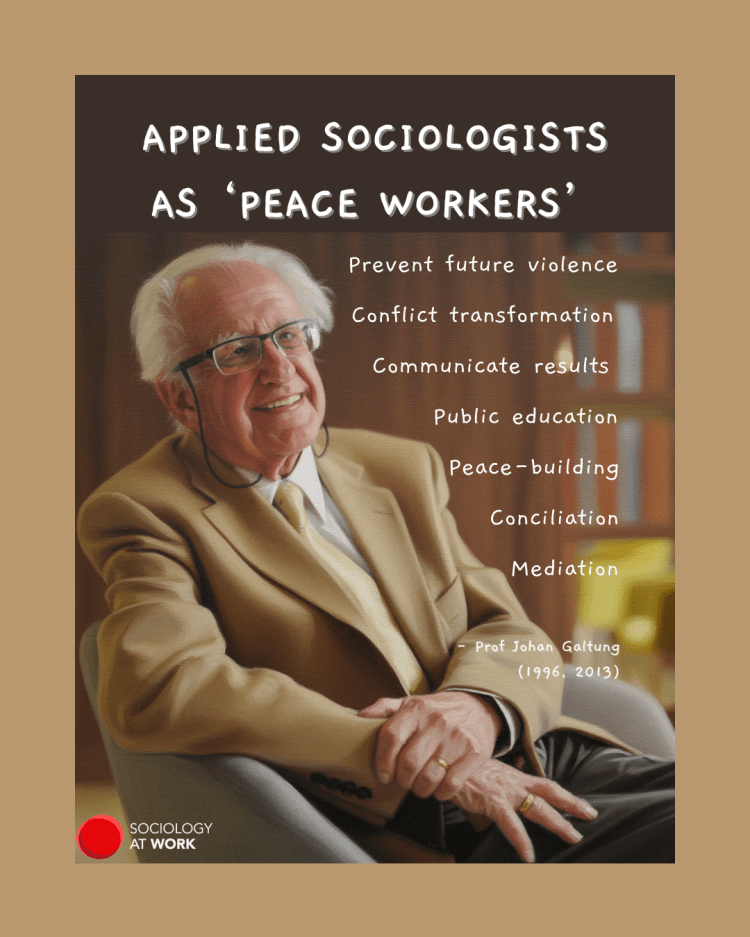

Applied roles

Galtung draws on sociology to establish three professional characteristics of peace workers:

- Skills: expectations that clients have about proven competence

- Code of conduct: rules governing relations between professional and clients

- Accountability: duties to clients and other professionals (2013: 121).

To describe the job, he suggests the terms ‘peace worker’ and ‘conflict worker’:

‘The workers should be skilled; but the unskilled are not ruled out. The point is to do an honest job, not to claim fame or to call a press conference – rather like the Catholic nun who acts but is neither seen nor heard.

‘Social workers seem to see themselves that way; health workers, at least in the lower echelons of the health professions, likewise. There is also a connotation of quantity: there could be many, even very many of them. Like a swarm of conflict and peace workers, unleashed upon a conflict until parties with violent inclinations give in, if for no other reason than to get rid of them. This may sound slightly violent, but far better than the naive alternative: some empty agreement signed at the top level, usually binding only on some highly forgettable ‘statesmen’ trying to substitute structural for direct violence.’

– Johan Galtung (1996: 266)

Peace practitioners might lead four processes:

- Mediation: facilitate solutions to current conflicts. Inform parties of how similar conflicts have been successfully resolved elsewhere. Offer sensible proposals

- Conciliation: ‘healing the effects of past violence,’ such as trauma

- Peace-building: ‘preventing future violence’

- Conflict transformation: use dialogue or other peaceful means by which to change attitudes (or images), behaviours, and contradictions (‘incompatible goals’). (2013: 13, 16).

Conflict transformation necessarily leads to a new social structure (1996: 116).

Applied skills

Galtung saw peace practitioners as doing more than academic research. This applied work also involves:

- Peace education: communicating the results of peace research

- Peace action: practising the findings directly with at least one party in an ongoing conflict (1996: 266)

Why, what, who, how, when

Galtung defines the purpose and methods of peace work (1996: 103):

Why: To stop further suffering and destruction, and arrive at a sustainable solution.

What: Peace workers can prevent and undo violence, achieving three key outcomes with applied peace negotiation skills (1996: 103, 270-271):

- Peace-keeping: support dialogue to stop destruction (‘control actors so they stop destroying things, others, and themselves’). Provide training for military de-escalation, for local populations, and leaders in conflict mediation techniques. This includes what say and do during meetings, including in hostile situations.

- Peace-making: change behaviour (’embed the actors in a new formation), and ‘transform attitudes and assumptions.’ Generate creative, timely, and sustainable solutions to conflict. For example, hosting conferences, using technology to proliferate ideas, and other means to diversify and democratise peace dialogue and practice across the world.

- Peace-building: ‘overcome the contradiction at the root of the conflict formation.’ Focus on ways to recognise opportunities for structural and cultural peace, and working towards positive transformation.

Who: Anyone can participate in peace work, including the state, civil society (organisations), private and transnational corporations, and individuals.

How: Through a communication process.

When: Any time, not necessarily with all parties at the same time.

With respect to peace-building, Galtung writes:

‘This means identifying exploitation, repression, and marginalisation (vertical structural violence) as well as groups that are too close to be comfortable with each other, or too far apart to interact symbiotically (horizontal structural violence). The vertical should be made more horizontal, and the horizontal more optimal.’

– Johan Galtung (1996: 273)

Ultimately, Galtung defines peace as achieving direct, structural and cultural peace. Thus, peace is a dynamic, ‘never-ending process’:

‘Peace is what we have when creative conflict transformation takes place nonviolently. Hereby peace is seen as a system characteristic, a context within which certain things can happen in a particular way […]. Three points are made in this definition: the conflict can be transformed (conflicts are not (re)solved) by people handling them creatively, transcending incompatibilities – and acting in conflict without resource to violence.’

– Johan Galtung (1996: 265)

Galtung sees conflict transformation as long-term work, with many peace workers chipping away at specific conflicts and structural problems over many years:

‘But peace is also an exercise in perseverance. Decades may pass before a good idea is implemented, if at all; and even if it is implemented the author may never know. For one thing, he may be dead by then; or the idea was co-opted by somebody who “had always been of that opinion.” Peace work is not a pathway to immediate gratification. The goal is peace, not publicity.’

– Johan Galtung (1996: 274)

Applied sociology outcomes

Some of the mediations that Galtung led include (2013: 15-19):

- 1971: Israeli-Palestinian peace plan, including Palestinian recognition and open borders

- 1971: Kashmiri independence movement, including greater autonomy, a Kashmir Free Trade Association with open borders, and a Kashmiri passport for locals

- 1975: North and South Korea dialogues, including the ‘sunshine policy’ to improve relations

- 1991: Former Yugoslavia proposals, and subsequent consultations in Belgrade in 1997

- 1995: Ecuador-Peru border dispute over the Andes Mountains border, contributing to the implementation of a jointly administered ‘binational zone with a natural park’ and free trade zones

- 1997-1998: Northern Ireland peace proposal, including self-rule, and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- 2006: Denmark dialogue with Islamic clerics, to end violent protests following publication of political cartoons mocking the Prophet Mohammad.

‘Peace appeals to the hearts – studies to the brain. Both are needed, indeed indispensable. But equally indispensable is a valid link between brain and heart.’

– Johan Galtung (Source)

Credits

Images

- Header: Original photo (with colleagues), remixed by Sociology at Work.

- Original photo (microphone), remixed by Sociology at Work.

- Original photo (bookcase), remixed by Sociology at Work.

- Original photo (couch), remixed by Sociology at Work.

- Original photo (headshot), remixed by Sociology at Work.

Discover more from Sociology at Work

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.